Written by Conservation Coordinator Shelby Serra

Fishing – from meager to monstrous

Fish as a means of nourishment have been an integral component of human history for millennia. However, in the last 50 years, annual global consumption of seafood products has more than doubled per capita2 as methods for fishing became more effective.

Since the earliest days of fishing, seafood preservation techniques have developed and transportation improved, with viable fishing shifting from small-scale local activities to major commercial enterprises1. In addition, boat design and construction advanced along with corresponding improvements in fishing gear and preservation, especially with the introduction of canning. Canning was a particularly important advancement, as it allowed for long-term storage and large-scale distribution1. Today, humans can fish anywhere, at any depth, for any species3.

Two predators, one prey

With the advancement of human capabilities and resultant increase in fishing efforts, we are beginning to see increased stress on whale and dolphin populations. Although the actual fishing for whales (whaling) was once a profitable industry, the “easy money” of the industry was short lived due to the rapid decrease in whale stocks4. Today, the commercial fishing industry’s unintended consequences impact the whales and dolphins of the sea.

The biggest concern as it pertains to marine mammals and fisheries interactions is bycatch. The U.S. Ocean Commission in 2005 judged incidental catch in fisheries as the “biggest threat to marine mammals worldwide… killing hundreds of thousands of them each year”8.

Figure 3. A false killer whale gets hooked on a fishing line

Bycatch represents the incidental catch of nontargeted species, resulting in mortality or series injury5. Although bycatch encompasses all incidentally caught marine life and is causing harm to many species of sea birds and sea turtles5, the use of the term “bycatch” in this article series refers to the incidental catch of marine mammals.

Although there are several forms of marine mammal and fisheries interaction, our focus is on those impacts and mitigation efforts that target operational or direct interactions in which marine mammals come into physical contact with fishing gear5. For example, a marine mammal may be injured or killed by becoming entangled or entrapped in fishing gear9. Another example of cetaceans falling victim to fishing operations, and a primary concern of PWF Ecuador Research Director Cristina Castro, is the use of marine mammals in fish aggregating devices, or FADs, which is illegal and could cause conservation problems for the target animals10. We will dive deeper into those implications in a future installment of this series. Finally, in addition to operational interaction, there are also interactions that occur when fishing gear is no longer active. This threat is commonly referred to as “ghost gear.”

Fishing gear – a delicate balance

To mitigate the impacts of bycatch on marine mammals, it is important to look at some of the gear types used in commercial fisheries, as some are more likely to inadvertently ensnare cetaceans than others. For example, gear types that are deep-set in the water column pose a higher risk to those cetaceans that move through those fishing grounds, simply because they act as an obstacle. It is important to evaluate harmful gear types employed by fisheries, both while the gear is actively in use, and later when it can become “ghost.”

According to a global assessment of fisheries bycatch, the physical and biological reasons for bycatch lie in three rationales. First, sometimes both the target and non-target species co-inhabit the same ocean space that is being fished16, meaning simply that because these fish are caught in the wild, there will likely be more than one species in any given space in the ocean. Second, the species may behave differently to fishing gear, causing unintended interaction for non-target species. For example, some species of cetaceans may remove or damage fish captured in the gear, known as depredation, possibly resulting in both economic loss to the fisherman and injury to the animal involved5. Lastly, the methods for gear use and the physical characteristics of the gear itself are not species- or sex-specific and, in some cases, not size-specific16, leading again to accidental catch. In essence, disparate animals react differently to various gear type. As fishing operations take place in a wild environment, all of these factors contribute to the unintended catch of other marine animals.

According to NOAA, to implement sustainable management practices to reduce bycatch, a variety of components need to be assessed, such as how gear is rigged, where it is deployed and from what type of vessel, navigational challenges and more17.

The Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) is the world’s largest cross-sectional alliance committed to promoting solutions to the problem associated with ghost gear globally. The GGGI created a best practice framework for the management of fishing gear, including a ranking of the risk gear poses after being lost, discarded or abandoned, and the impact this gear would have on the environment11.

Ranked number one on the list with the highest likelihood of abandonment and highest impact once abandoned is the gillnet11. Gillnets are a single wall of netting which can either be fixed or allowed to drift and catch fish by enmeshing or entangling them, usually around their gill covers11. Gillnets can have high rates of loss. Many are set in areas with strong tidal or other currents, further exacerbating their susceptibility to accidental loss. In addition, most gillnet fisheries are confirmed to have cetacean bycatch8. Although this gear is ranked highest risk and biggest impact once abandoned, there are many studies that show this gear also poses a risk to cetaceans while being actively employed by fishing operations. Gillnets are considered a type of “passive” fishing effort, as the nets are placed in the water, left to fish and retrieved later6. Direct interactions between marine mammals and fisheries occur much more frequently with passive fishing gear, particularly gillnets, than active because a fisherman is not under direct control of the gear6.

Gear with the second highest risk for negative impact are traps and pots11. Traps and pots are a collective term that refer to structures used primarily by crustacean fisheries whereby the target catch is enticed through funnels that encourage entry but limit escape11. Since these mechanisms are attached by rope or line from the pot or trap to the surface, large marine mammals are at risk for entanglement in this type of gear.

Both gillnet and trap/pot fisheries are responsible for a significant portion of large whale bycatches6. According to NOAA, trap/pot fisheries in the U.S. pose the highest risk to the North Atlantic right whale due to this rope/line suspension in the water column in areas where these critically endangered whales19 often feed, calve and transit14. Due to the immense amount of data connecting fisheries interactions and the declining population of North Atlantic right whales, NOAA formed the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Team to impose stricter regulations on the “take” allowance for fisheries13. We will expand on how NOAA and other agencies use science to formulate these regulatory conclusions, including the formation of Take Reduction Teams, in our next installment of this series.

A harmful ghost

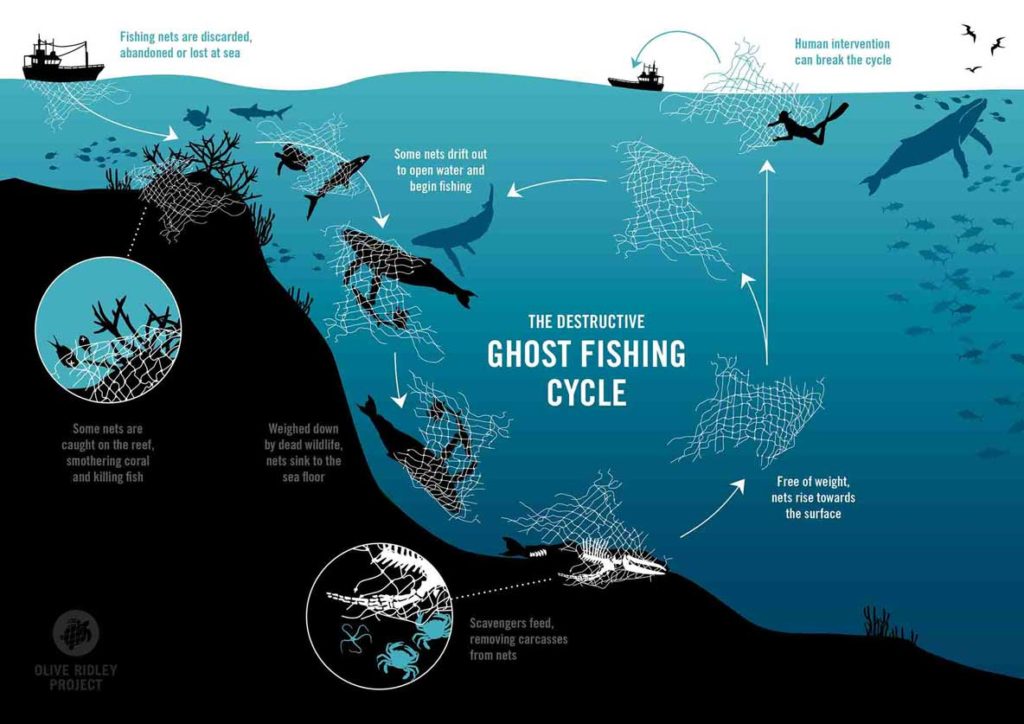

Once active fishing gear has been abandoned, lost or discarded, it becomes “ghost gear.” NOAA groups major gear losses into four categories of general contributing factors: environmental, gear conflict, gear condition and inappropriate disposal at sea14. Gear types that drag behind a vessel, such as bottom trawls and deep-set gillnets, can snag on a reef or rocky bottom that leads to loss11. Gear types made of weaker materials can become lost due to bad weather or storms or can potentially get tangled in themselves. Due to the small financial loss to the fishery, the gear is often abandoned and discarded11.

But how is ghost gear particularly harmful to cetaceans? According to the International Whaling Commission, at least 300,000 cetaceans die in fishing gear every year, equating to 800 whales, dolphins or porpoises each day. In fact, an estimate based on bycatch data from U.S. fisheries revealed global marine mammal losses to be over 650,000, when pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) are considered5. Whales and dolphins are thought to be especially vulnerable to the effects of bycatch mortality because their long life span and low reproductive rate limits the capacity of population recovery18. Many cetaceans are migratory, meaning they spend several months each year traveling from one area to another, often covering vast distances in search of food, a particular climate or a safe breeding ground8. In addition, there are some behavioral factors that play a role in increasing the risk to some cetaceans. According to one behavioral study of cetacean reaction to unknown elements in their environment, frightening, novel or unexpected stimuli can encourage close-range investigation12, which can lead to the incidental entanglement or capture of that animal. From a conservation management perspective, these facts make cetaceans vulnerable to a wide variety of threats because they are not confined to one space in the ocean, species and behavioral variation, and variations in protections from region to region.

How can we mitigate?

Because of the variation in the ways gear can be lost, and many differences in regional governance, there is naturally great variation in possible solutions to prevent bycatch and further “ghost fishing” impacts on the marine environment. In the next installment of this series, we will be looking into some of the regulatory arms involved in fisheries management as well as any mitigation legislation currently in place to try to minimize the impacts to whale and dolphin populations. Stay tuned!

Fisheries Interactions Part 2 found HERE

View more Pacific Whale Foundation Making Waves article series HERE.

References

- Lackey, Robert T. 2005. Fisheries: history, science, and management. Pp 121-129. In: Water Encyclopedia: Surface and Agricultural Water, Jay H. Lehr and Jack Keeley, editors, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., Publishers, New York, 781 pp.

- Guillen, J., Natale, F., Carvalho, N. et al. Global seafood consumption footprint. Ambio 48, 111–122 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1060-9

- Gewin V (2004) Troubled Waters: The Future of Global Fisheries. PLoS Biol 2(4): e113. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020113

- Coleman, J.L. The American whale oil industry: A look back to the future of the American petroleum industry?. Nat Resour Res 4, 273–288 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02257579

- Read, Andrew J., et al. Bycatch of Marine Mammals in U.S. and Global Fisheries. Conservation Biology, vol. 20, no. 1, (2006), pp. 163–169., doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00338.x.

- Read, A. J. (2005). Marine mammal research: Conservation beyond crisis (pp. 5-17) (1133696556 854498720 J. E. Reynolds, Author). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

- Alverson, D. L., M. H. Freeburg, S. A. Murawski, and J. G. Pope. 1994. A global assessment of fisheries bycatch and discards. Fisheries technical paper 339. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome.

- Young, N.M. and S. Iudicello. 2007. Worldwide Bycatch of Cetaceans. U.S. Dep. Commerce, NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-OPR-36, 276p.

- Read, A. J. (2008) The looming crisis: Interactions between marine mammals and fisheries. J Mammal 89: 541–548.

- Castro, C., Van Waerebeek, K., Cárdenas, D., and Alava, J. (2020). Marine mammals used as bait for improvised fish aggregating devices in marine waters of Ecuador, Eastern tropical Pacific. Endanger. Species Res. 41, 289–302. doi: 10.3354/esr01015

- Huntington, T. (n.d.).(2017). Development of a Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear (pp. 8-47, Rep.). Poseidon Aquatic Resource Management.

- Bowles, A.E., Anderson, R.C., 2012. Behavioral responses and habituation of pinnipeds and small cetaceans to novel objects and simulated fishing gear with and without a pinger. Aquat. Mamm. 38, 161–188.

- fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england-mid-atlantic/marine-mammal-protection/right-whales-and-entanglements-more-how-noaa

- NOAA (2015). Impact of “Ghost Fishing” via Derelict Fishing Gear (Rep.). Silverspring, MD: Office of Response and Restoration.

- Kravec, Nicole. Standford University. (2019, August 20). Food security from oceans. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://news.stanford.edu/2019/08/20/food-security-oceans/

- Alverson, D.L., Freeberg, M.H., Pope, J.G., Murawski, SA., 1994. A global assessment of fisheries bycatch and discards. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 339. Rome, FAO. 233pp

- Lambert, D.M., E.M. Thunburg, R.G. Felthoven, J.M. Lincoln, and W.S. Patrick. 2015. Guidance on Fishing Vessel Risk Assessments and Accounting for Safety at Sea in Fishery Management Design. U.S. Dept. of Commer., NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OSF-2, 56 p.

- Brown, S. L., Reid, D., & Rogan, E. (2013). A risk-based approach to rapidly screen vulnerability of cetaceans to impacts from fisheries bycatch. Biological Conservation, 168, 78-87. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.09.019

Image Sources